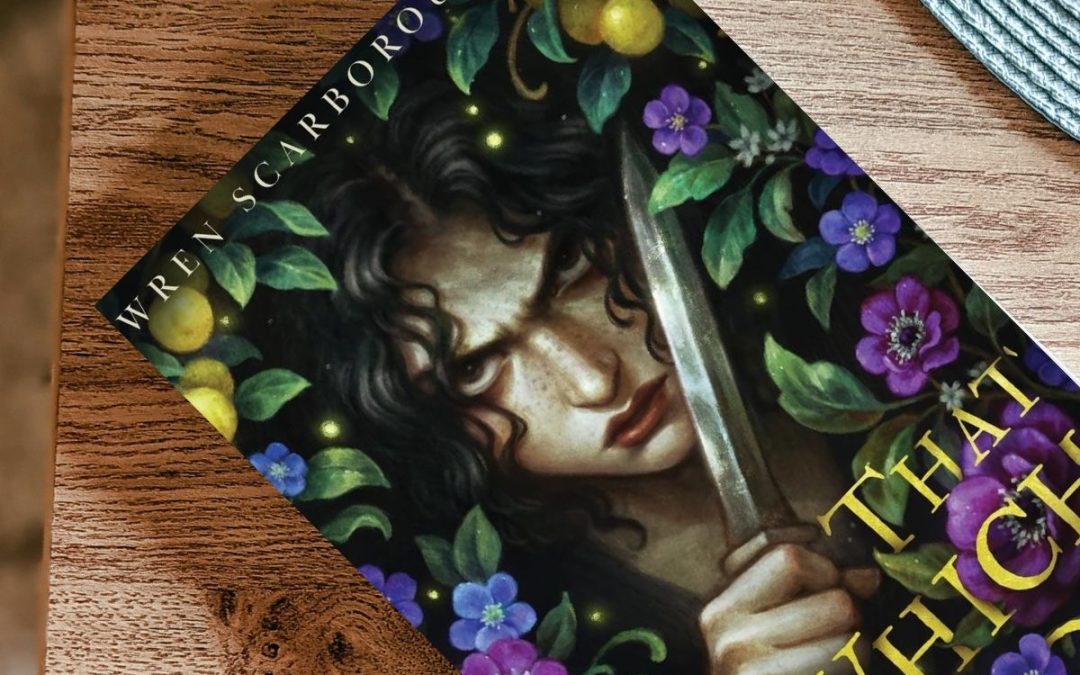

In October 2024, Wren Scarborough self-published That Which Sings an action-packed Young Adult Fantasy novel. We sat down with Wren to discuss her new book, her perspective on fairy tales and her own unique approach to writing fantasy.

Interview by Franz-Herman Krauel

This interview was published in a shortened version in the 172. issue of moritz.magazin. You can find the issue with other articles online here, or in physical form in our libraries, canteens and other university buildings.

moritz.magazin: That Which Sings is a “punk rock fairytale”. What makes a punk rock fairytale and what inspired you to write one?

Wren Scarborough: The term “punk-rock fairy tale” actually came after writing the book. It was coined by my friend and reader Grace a few drafts in, at which point I informed her that I would be stealing it for marketing purposes. She may have her own definition, but as a lover of both the punk spirit and fairy tales, I think of it like this:

Firstly, it must have at least the bones of a fairy tale: escapism and adventure, peril and comfort, enchantment and the eucatastrophe. It must take place in Faerie, the realm we are summoned to by the words “once upon a time”, where magic is a simple fact of reality and we do not question why the Wolf speaks or the Giant may take his heart from his body.

Secondly, it must be animated by the values of the punk – the real, proper punk, not just anybody who wears leather and spikes and listens to loud music (and in fact, conformity to the punk aesthetic for the sake of it is completely the opposite of punk). The willingness to be thoroughly and unapologetically oneself regardless of societal pressures, furthermore to rebel against oppressive establishments and authorities, and to suffer the consequences.

To be frank, fairy tales are already pretty punk. They are stories for those who already know the world is rife with monsters, but need to hear that the monsters can be defeated. That even when it seems hopeless, it is your solemn duty to carry on, to endure and to fight to whatever end awaits you.

You’re a big fan of C. S. Lewis (author of the Chronicles of Narnia). Does his work inspire your own writings?

Indirectly, yes, and there are several scenes in That Which Sings where I noticed that inspiration coming through. I’ve never found myself actively drawing from the works of C. S. Lewis, but I love him dearly, and everything I love comes up one way or another in what I write.

The worldbuilding in That Which Sings is very immersive. The magical world of Elphame (setting of the story) feels very alive (often in a literal sense) and the Faeries are very different from the popular image of what a fairy looks like. What’s your worldbuilding process like?

My process is very… maybe “organic” would be the word. I’m not a worldbuilder by nature, those Tolkien (author of Lord of the Rings) types who actively delight in constructing a world down to the smallest details. I love and appreciate hard worldbuilding like that, but I am and have always been a soft worldbuilder (perhaps another area of Lewis’ influence).

I feel things out; I go where the story takes me. I knew I needed Elphame to be beautiful, lush, dangerous, and not quite right. There had to be something uncanny to every aspect, some edge to all that beauty that could be frightening or sickening or mysterious. I also knew I didn’t want my faeries to be either stuck in ancient or medieval times, or overly modernized, and that I needed them to still feel deeply folkloric. I drew from folklore, but played with it freely—the glossary exists in part to clarify how the fae of my Elphame work, not just to explain the basics of what they are in mythology and folklore. So while I did know going in several essentials to the world, mostly I was feeling it out, wandering through Elphame just as much as Nes herself.

The book is thrilling and surprisingly fast paced. How important is pacing to you as a storyteller?

I do think good pacing is essential to making a story work, if only to keep the reader from putting the book down, but good pacing is not necessarily fast pacing. A slower, lingering book can be paced perfectly; it just needs to keep up the tension to continue pulling the reader along. That Which Sings does start rather slowly, all things considered. There’s a long, tense buildup before the action kicks in and immediately starts escalating. This is the kind of thing you feel out, especially with help from your beta readers and critique partners to let you know that hey, Wren, turns out it is actually possible to spend too long describing a faerie market.

The fight scenes in the book oscillate between being delightfully brutal and horrifying. What’s your approach to writing action scenes?

I love writing action scenes, which is probably obvious to anyone who’s read the book. The trick to them is to understand they’re just a collection of moving parts, so as soon as you create a system to track those parts they become far easier to write. I did actually write an extensive Substack post on this, but to summarize:

Know your opponents, weapons, terrain, and how those relate to each other. Take them one movement at a time, like you’re choreographing a dance. Track movements, wounds, and ammunition of multiple opponents by visualizing the scene, either by acting it out or creating the fight in miniature with anything from LEGOs to labeled corn kernels and beans. Figure out when to disorient your reader and when to show them exactly what’s happening. Write out the beats and then flesh them out into prose.

It might sound like a lot, but again, once you have a system it starts to become simple. And really, really fun.

The delightful brutality and the horror are mainly determined by the tone the story calls for at that moment, as different action scenes have different implications. Either one, though, is the result of me enjoying myself a little too much and asking myself just how far I can take this.

Throughout the story, Nes (the protagonist) turns into a bit of a badass. At the same time, she is very vulnerable and suffers through much physical and emotional pain. How important was it to strike that balance between Nes’ badassery and her vulnerability?

Absolutely essential. When I first had the vague notion of this story I was probably around fourteen or so, and a sixteen-year-old girl going on a perilous adventure sounded like an exciting romp and hardly anything more. When I actually sat down to write the story a few years ago, though, I understood that Nes, whatever else she may be or become, was first and foremost a child, and that her story was not so much one of adventure but of a terrible and costly necessity.

One of my rules for writing the book was, “No one is allowed to forget she’s a child.” The only exception to that rule was Nes herself. She could forget, she could tear herself apart and attempt to reforge herself into whatever thing would best complete her mission, but the rest of us, even the faeries, must see the little girl underneath it all.

You argued that it’s essential to the story that Nes is a girl. Could you elaborate on that point?

Could I? Excessively. But it’s a little tricky to do so properly without getting into spoilers.

The most basic aspect of this book’s premise, the rescue/vengeance mission, is the sort of story one usually expects to have a male lead. A lot of the struggles – the physical ones, anyway – which Nes suffers are the sort one is more used to seeing a male character going through, and the sort more easily stomached when it is a man, or even a boy, enduring them. We send real, flesh-and-blood teenage boys into war; we have done so since the dawn of time. We are accustomed, in a sense, to subjecting men and boys to certain kinds of horrors. To subject a woman or a girl to them is something else.

In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Father Christmas says that “battles are ugly when women fight.” I found myself dwelling on that quote while writing this book, in part because it’s often misunderstood. It does not mean that women must not fight, or that women make fighting ugly, or any other reactionary interpretation. It means that it is a terrible, hideous thing for circumstances to become so dire that women must fight, that it is unnatural and disordered for women to engage in mortal combat even when it is necessary. Nes suffers in That Which Sings what she, as a girl, is not meant to suffer, but it becomes necessary for her to do so. That alone makes her being a girl essential to the story.

Nes’ girlhood infects endless aspects of the book, in large part because a girl is the thing she cannot allow herself to be. She cannot be soft or gentle or merciful. She cannot hold on to her own feminine weaknesses – which might not sound so bad, unless you understand what must be let go with them. It affects character dynamics, and that’s not even limited to those we see: Nes is her father’s daughter, and to be your father’s daughter is not the same as to be your father’s son.

But it would be essential no matter the story. Being a girl is essential to the story of any girl, just as being a boy is essential to the story of any boy.

Are you already working on a new writing project and would you write a That Which Sings-sequel?

Yes! And never!

The new book is referred to publicly only as 5th Side at this juncture, and it’s quite a bit different from That Which Sings in a lot of ways. A slower, softer, far less straightforward book with a protagonist rather unlike Nes. But of course it’s still me; it’s still filled with strange entities and brutality and fairy tale logic. It’s giving me a hard time, but all the same I’m very much enjoying myself.

Everybody asks about (and a few readers have been lobbying for) a sequel, but That Which Sings was always meant to be a standalone story. I feel I’ve put Nes through more than enough, thank you very much. And anyway, were I to actually continue her story in a sequel, I’m quite sure it would be an almost entirely separate genre from the original story. I’m not sure how many people would be up for that.

I do, however, intend to return to the world of That Which Sings. I didn’t write that glossary for nothing. Elphame and I aren’t done with each other yet.

How can people support your work?

The first thing, of course, is to read the book. You can find That Which Sings on Amazon, or order it from your local library or bookstore. After that, leaving an honest review makes a huge difference, and I do mean an honest review. It’s easy to get the idea that you’re only helping an author if you leave them a four or five star review, but in reality it helps way more to have a lot of varying reviews than a few glowing ones. Plus, what you dislike in a story will likely appeal to another reader, and may even convince them to give the book a shot. Tell your friends and family about it, suggest it for your book club, suggest it to your favorite book reviewer – anything that helps make people aware of it can help.

Thank you for the interview.

Beitragsbild: Wren Scarborough / ikigloo

Wren’s approach to blending fairy tales with punk energy is fascinating—her world feels alive, unpredictable, and unapologetically unique. It makes me want to dive into That Which Sings just to explore Elphame and its thrilling, beautifully dangerous magic!

Great advice—honest, varied reviews and word-of-mouth really do more to help a book find its audience than just five-star ratings.